I have been on a summer hiatus, doing some traveling and working in Turkey for Deaflympics and some other small trips within the United States. Now that I am back, I want to be more committed to this (blogging). While visiting Baltimore today, I remembered a facebook post that I came across recently.

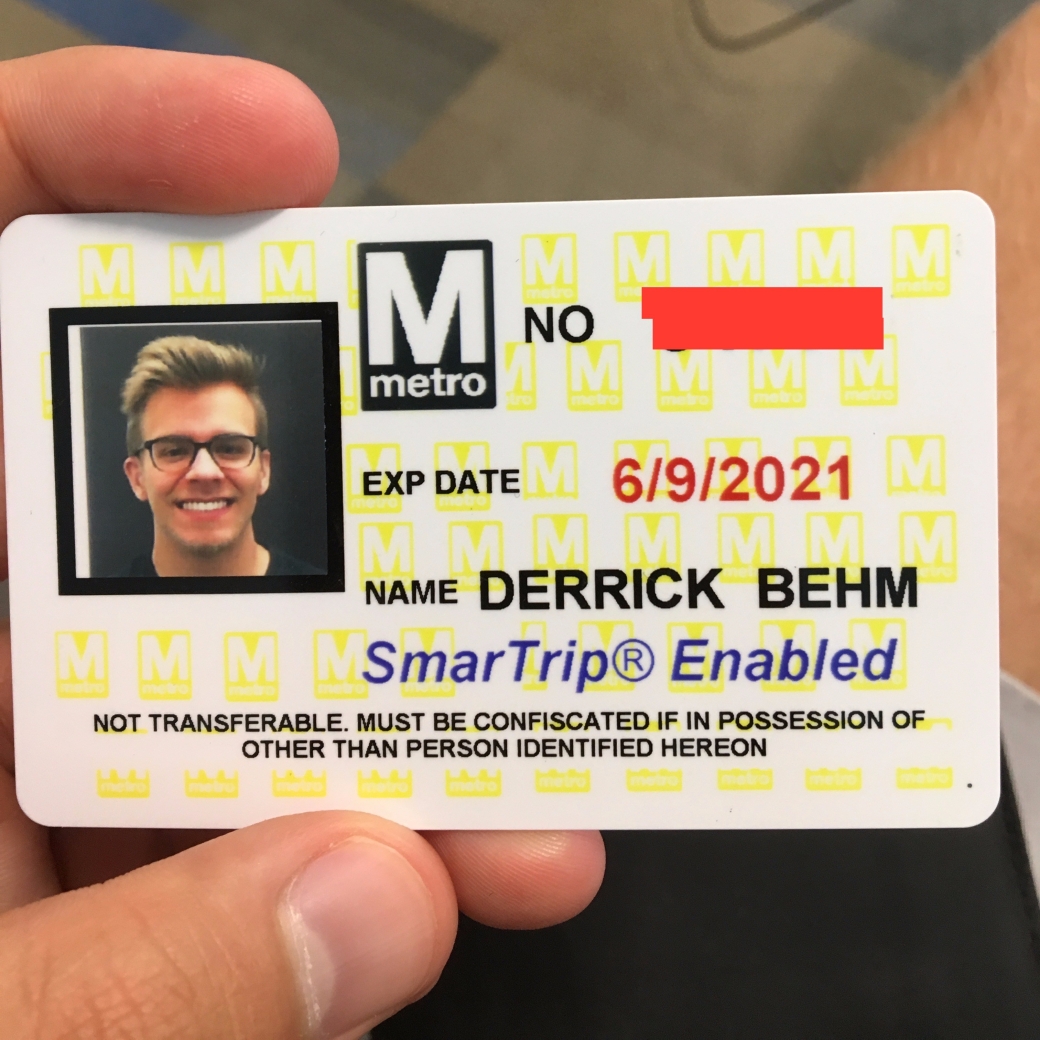

Disclaimer before I share the post: I have a Reduced Fare SmarTrip card for DC’s metro because I have a disability (just for being Deaf). This means that the prices for my trips are the same as what Senior Citizens pay for theirs. More information here: https://www.wmata.com/service/accessibility/reduced-fare.cfm

[Image description: SmarTrip Metro Card. Derrick’s portrait is on the upper left corner with a “M” Metro logo next to it. The card number is covered in red box for privacy. EXP DATE: 6/9/2021. Name: Derrick Behm. text at bottom of card: “SmarTrip Enabled, not transferrable. Must be confiscated if in possession of other than person identified hereon.” Background is blurred, but fingers are holding the card.]

The post:

“So I was feeling a little guilty about getting reduced fare (1/2 price off for people who are disabled) for the commuter train today, because I don’t generally feel like I really have a “problem”. But then when I went back to the train station to go to work from the disability certification office …

I’m sitting there waiting for my train, but I don’t know which gate to be at. I go to the gate it usually comes through, but nothing. I go back to look at the announcements, and it says the train is at this gate. So I go down to get on the train, but it’s not on the track it was supposed to be on. The doors are closed, so I couldn’t even get on if I wanted to. I’m confused. It leaves. It was my train.

So I go back into the station and think about what to do, because I’m in Baltimore and I need to be in DC pronto. If I wait for the next train, the same thing would probably just happen again. Finally, I decide to just take Uber because the cost I save on riding the train with reduced fare way negates the cost I have to pay for Uber anyway.

While riding Uber for the hour it takes to drive from Baltimore to DC, I thought about my experience riding the commuter train for the last eight years. I thought about how much I actually have to plan all the traveling I do, like only getting on at easy-to-navigate stations along the route to make sure that I never miss the train because I didn’t hear the announcement. I thought about how long it took me to order my reduced-fare ticket because I had to write back and forth instead of just talking directly to the attendant (but the attendant was very nice, anyway, thankfully). I thought about how I had to get yet another audiogram in order to prove I was really deaf to get the discount, and the audiologist barely even said a word to me and basically tried to sweep me out of his office as quickly as possible — and when he did say something, he opted to speak instead of write, even though I told him over and over again to write. I thought about that one time I missed my stop because I fell asleep and couldn’t hear the announcement, and none of the conductors bothered to wake me up to tell me that it was the last stop. I thought about how, when I went to tell the conductors that I missed my stop and we were already halfway back to DC, they all looked at me with the most pitiful stares I’ve ever seen — and let me tell you, I’ve seen quite a few.. I thought about that one time I had to get off the train to board a different train, and the only reason I knew I had to get off the train was because literally everyone was getting off the train. I thought about how when the train dropped us off at an earlier stop than mine, I didn’t know what to do because no one wanted to explain it to me, so I just followed everyone else into taxis and hoped I’d get where I needed to go. I thought about how, if I want to know if the train is delayed while sitting on the train, I have to go online and hope they updated the service status (but they usually don’t) — or look outside the window and hope to glimpse one of the signs saying how many minutes the train is delayed by (but those signs are near-impossible to see and read in a moving train). I thought about how many conductors selling me a ticket have sighed exasperatedly and rolled their eyes at me when they realized that I was deaf.

I can’t say I feel guilty anymore. I mean, you guys, my life is pretty amazing, but it’s also full of a hell of a lot of annoyances. Not because I’m deaf, but because the way the world works, more often than not, leaves me out because I don’t hear. In the end, that’s what makes a person disabled — not that they “can’t do something”, but that the world doesn’t work for them in the same way that it works for everyone else.

So, in the end, I was right: I don’t have a problem. The problem isn’t mine; instead, it’s how the world works.”

[End of transcript]

I have several stories similar to this. One of them… [the excerpt below is signed in ASL, and the video can be found here]

On New Year’s Eve 2007/08, five of us—including my brother—went to NYC to see the ball drop. It was a fun, long, exhausting day, and on our 1am Metro-North train out of Grand Central to Beacon (upstate NY), I just wanted to sleep. My eyes were already irritated from wearing eye contacts for too long, so I took them off. My brother would be the one driving home from the Beacon train station, so I didn’t need my eyes for driving or anything, but if you must know, everything becomes blurry beyond two feet.

So, when my brother, Cory, woke me up with a jarring shake on the train, asking me if we were at our stop (Beacon), I was so disoriented. I looked out the window, and everything was blurry, but that didn’t matter because even so there was no sign in sight, but somehow I registered that this was our stop and nodded. By then, it was too late, the train started moving. The five of us missed our stop. Of course we didn’t hear the announcements of stops, we were all Deaf.

I wear hearing aids. While I cannot always make out what the announcement says, I at least would be able to hear something to pay attention or wake up—but that early morning, my hearing aid batteries died with 2007, just when everyone screamed their welcome to 2008 and killed my batteries.

At the next stop, we had assumed it would be Poughkeepsie (a city with urban grid) and got off. But it was New Hamburg, a stop that none of us had ever been to. It was essentially in the middle of the woods and some homes—in other words, nowhere. It was 3 am.

It was the time of sidekick 2 or 3—I can’t remember which. We didn’t have phone service (because we were all on the “Deaf plan” where we have no phone service and only use text and data), so we couldn’t call home and wake up our hearing brother. Everyone at home went to bed after we told them that we got on the train safely.

Cory had me ask someone what time the next train going in the opposite direction would come. I was tired and mad, especially so because I couldn’t hear or see, but somehow we found out that the next train would come at 5:30 am. This was not good news because we didn’t want to wait for more than two hours in the freezing January weather.

Remember, this was before Uber. Also remember that calling for taxi was not a “Deaf friendly” thing to do since there are no TTYs or VideoPhones at places where you are most likely to call for a taxi. In other words, we couldn’t hail a ride to get back to the Beacon train station.

There was a police car by the station, and we were getting a bit desperate. I think maybe Cory thought I was young and cute enough to ask for free rides (I was 16 but looked 14), so I asked. He shook his head, “Only in handcuffs I can give other people rides.” Cory actually offered to be handcuffed, but the policeman didn’t budge and told us off.

Frustrated, the five of us decided to walk down the only road out of the station, hoping to find some convenience store or something, but there were only homes. Cory and a friend wanted me to go knock on a house that had a party still going (lights on inside, many cars outside, etc), and ask for a ride. I flat-out refused, I was already mad at this point.

[side note: even after telling them that you are Deaf, 99% of the time speaking to hearing people, they will talk back as they normally do, blurring one word with the next with no additional effort in communicating with gestures or speaking clearer. When I was young (and ignorant), I would tell people that I was Deaf and keep trying to talk and hope that the other person would improve how they talked so I could understand… 99% of the time it didn’t work and 100% of the time it irked me. This is one of the big reasons why I stopped talking—it forces people to recognize that I need another way of communicating. On that morning, I didn’t want to experience this—especially so being vulnerable without my glasses/contacts and hearing aids.]

Cory and his friend actually knocked on two houses and asked for rides, and they told them “sorry.” We gave up and turned back to the train station. As we approached the station, we saw the train come, and we ran… but train left just as we got on the platform. As you might imagine, I wasn’t happy about that, but the girl I was with managed to bring some humor in the situation and I just let go of the whole thing. Nothing we could do but call it an adventure.

We waited another hour and got on the 6:30 am train. The train conductor almost had us pay another ticket, but I forget how we convinced him to let us off the next station without paying. I just remember feeling a huge relief when I got home and put on my glasses for the short time before going to sleep at 7:30 am.

Some takeaways from this blog so far:

- The world operates on a system that does not benefit people with disabilities (i.e. voice announcements are not accessible for Deaf people. Visual announcements alone are not accessible for Blind people. Both voice and visual announcements do not benefit DeafBlind people).

- Technology 10 years ago sucked, and today it is so much better for us (I love Uber, for instance), but we still have so much to improve on. I believe 10 years from today will be much better if we continue advocating for a system that benefits EVERYONE.

- In the meantime, it is justified that “able-passing” disabled people get the Reduced Fare SmarTrip Card; and it is not justified that this card compensates for lack of trying to make public transportation accessible for everyone.

After reading that facebook post I shared above, I came across another post by another guy in the UK, who also shared his frustration about trains. His link:

https://thedeaftraveller.com/2017/08/22/are-uk-trains-deaf-friendly/

He talks about how trains can improve—in other words, he is telling how the world should work better to accommodate Deaf people.

In closing, I want to give credit/my support to WMATA and other agencies that work daily to ensure that public transportation services continue to improve for the benefit of everyone, including people with disabilities.